A number of projects that we are involved with have led to some musings on agriculture, trade, environment and development. We decided to post some of these thoughts, which will be published in three parts: this entry focuses on global trends.

There is a lot of focus on the issue of how agricultural production influences the communities and environment in the countries of origin. Naturally, a lot of the discussion in ‘the North’ has been about the products we import from emerging economies. This is understandable, because it’s easier to influence companies that have to protect their brands among European and American consumers. Civil society organizations have successfully influenced ‘pull’ trade policies such as Greenpeace’s ‘Kit Kat campaign’ on palm oil – which probably contributed to the European Community policies on palm oil traceability, as well as sustainability commitments by major food & beverage players.

It’s very clear that more needs to be done on trade policies. But, we also feel that more attention needs to be given to domestic developments. In particular to address growing concerns about food security and health issues amongst the emerging, younger, middle classes in many of up-and-coming economies – be it the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa), MINT (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, Turkey) or the PINE (Philippines, Indonesia, Nigeria, Ethiopia) countries. Many of these countries have an increasing demand for safe, healthy, agricultural produce. Focusing exclusively on emerging economies as ‘producer countries’ and the EU or US as ‘the consumers’, or framing the ‘private sector’ as international companies fixated on international trade could, at best be shortsighted, and at worst, be interpreted as neo-colonialist.

I was reminded of this in a recent article I read on FreshPlaza: This article summarized a problem faced by horticultural producers in Viet Nam, where local consumers were rejecting high-quality vegetables for fear that they were Chinese imports, with high levels of pesticide residues.

Its practically impossible to have a discussion on agriculture these days without mentioning the famous (or, the ‘infamous’) FAO figures predicting that a growth in the worlds’ population to 9.1 billion by 2050, will require a 70% increase in food production. Regardless, considering the basic arithmetic its highly likely that as a species we will be demanding more food, and that this food will be more resource-intensive foods. And, that in order to minimize adverse impacts, this food should be produced in the most resource-efficient manner, be it for export or for local consumption. Demand growth is also most likely to come from ‘the new middle classes’ in Asia, Latin America and Africa, rather than Europe or the US.

At the same time, the global environment is changing, and these changes are being manifested locally in different ways. This is happening at the same time as a narrowing of diversity of consumed agricultural products. To quote from Khoury et al (2014):

“The increase in homogeneity worldwide portends the establishment of a global standard food supply, which is relatively species rich in regard to measured food crops at the national level, but species-poor globally. These changes in food supplies heighten interdependence among countries in regard to availability and access to these food sources and the genetic resource supporting their production, and give further urgency to nutrition development priorities aimed at bolstering food security.”

This modification of our global resource base, the push and pull factors, and their consequences are something that needs to be considered. We need a refined discussion on the issue of agricultural ‘stranded assets’[i] that includes industry representatives and considers issues such as domestic food safety and security concerns, infrastructure capacity and homogenization of global diets, as well as climate change and biodiversity.

To give you a relevant visual image of this, see this snapshot from the Khoury et al (2014) paper:

Figure 1: “Global change in similarity (homogeneity) of food supplies, as measured by Bray-Curtis dissimilarity from each country to the global centroid (mean composition) in each year, converted to similarity. (A) Global mean change in similarity to centroid of national food supplies. Points represent actual data, and lines are 95% prediction intervals from linear mixed-effects models. (B) Multivariate ordination of crop commodity composition in contribution to calories in national food supplies in 1961, 1985, and 2009. Red points represent the multivariate commodity composition of each country in 1961, blue points in 1985, and black points in 2009. Circles represent 95% CIs around the centroid in each year. Between 1961 and 2009, the area contained within these 95% CIs decreased by 68.8%, representing the decline in country-to-country variation of commodity composition (i.e., homogenization) over time. (C) World map displaying the slope of change in similarity to centroid of national food supplies for calories.” (Khoury et al, 2014).

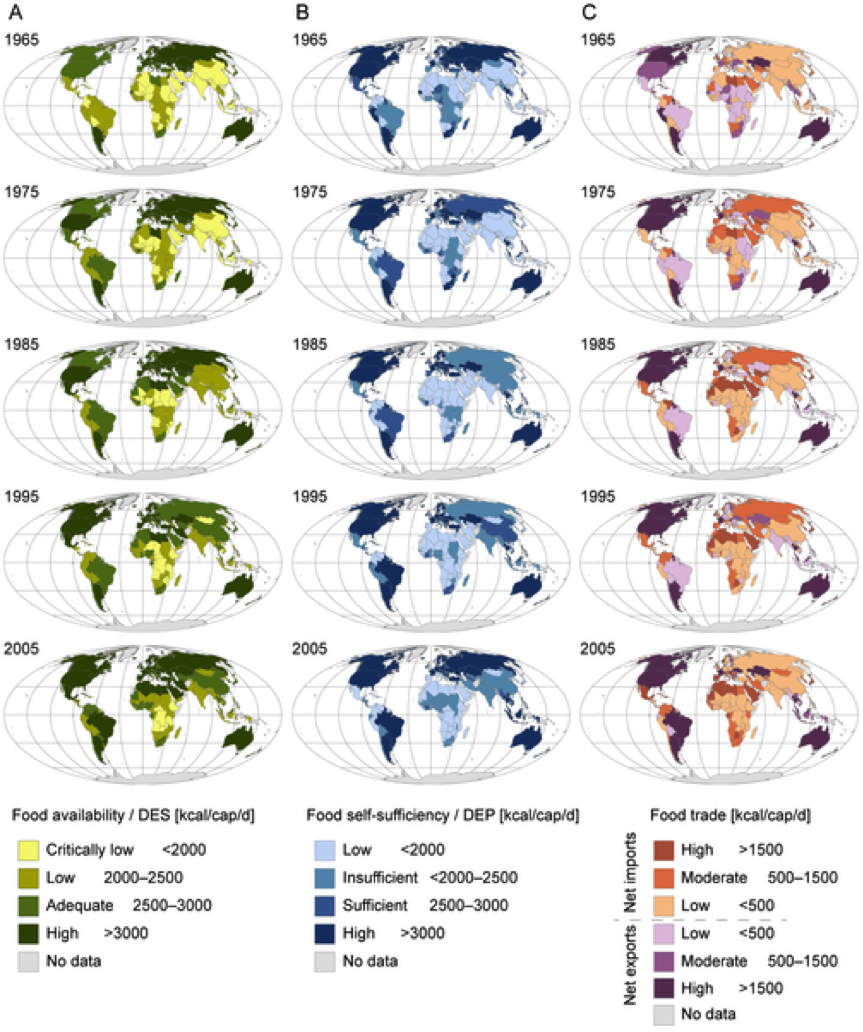

I’ve also added an image below that I came across recently, which should set the scene for the next part of this post.

For now, the key messages seem to be that:

- Internationally, diets are becoming more homogeneous. While this allows the global food system to become internationally ‘commodified’ this clearly also increases risks, as production disruptions have the potential for global contamination.

- Some areas with growing populations have seen increases in food insecurity, which may also magnify risks i.e. of Governments imposing populist policies and trade bans of key commodities.

These issues aren’t necessarily related. They clearly also need to be considered carefully within the local context, but, they do raise the issue with respect to global trade, a topic that we cover in a following post.

[i] Generation Foundation coined the term ‘stranded carbon assets’ in 2013, which highlighted risks associated with investing in carbon-intensive assets (http://genfound.org/media/pdf-generation-foundation-stranded-carbon-assets-v1.pdf). University of Oxford & SSE later published “Stranded Assets in Agriculture: Protecting Value from Environment-Related Risks” (http://www.smithschool.ox.ac.uk/research/stranded-assets/Stranded%20Assets%20Agriculture%20Report%20Final.pdf), but this reported should probably only be considered a first step in considering this important issue.